The Supreme Court Takes Up “Skinny Labels” and the Fantasy World Where Generics Don’t Compete

If you were under the impression that Congress created section viii[1] so generics could come to market with unpatented uses of branded drugs without being sued for encouraging infringement of patented uses, the Federal Circuit would like a word. Remember the ole’ days of Warner-Lambert Neurontin®[2] when the Federal Circuit slavishly followed only the words on the label in deciding whether a generic applicant’s “skinny label” induced infringement? Well, in 2021 the pendulum swung in GSK Coreg®[3] and just like that induced infringement received a booster shot to consider not only the label, but also the generic applicant’s marketing efforts, catalogs, and press releases.

Ever the pot-stirrer, the Federal Circuit promptly went further, and now the Supreme Court has been asked to sort out whether a fully carved-out generic label—plus the audacity to call a product “the generic version” and to cite public sales data—can plausibly amount to encouraging doctors to infringe. The Solicitor General says “no,” market reality says “no,” and basic statutory structure says “no.” Yet, here we are.

The Petition That Finally Put “Skinny” Back in Skinny Labels

The concept of a “skinny label” is pretty simple. Where an innovator sells a drug with a patented use and an unpatented use, a generic may avoid the hassle of a lawsuit by selling a generic version with a skinny label carving out the patented use.

Enter induced infringement. And creative lawyers.

The case is Amarin v. Hikma.[4] The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Hikma’s ANDA for a generic version of Vascepa® with a true section viii carve-out: the label included only the unpatented severe hypertriglyceridemia (SH) indication, deleting the patented cardiovascular risk-reduction (CV) indication. No instruction to reduce CV risk. No statin co-therapy guidance. No wink, no nod.

But a funny thing happened on the way to the Forum: Amarin sued anyway. Not because the label instructed the patented use—both the district court and the Federal Circuit agreed it didn’t—but because Hikma had the temerity to:

Call its product the “generic version” of Vascepa.

Note that Vascepa’s sales were, well, large.

List “Hypertriglyceridemia” as the therapeutic category on a web page, while including a disclaimer that the product was approved for fewer than all Vascepa uses.

According to the Federal Circuit, that cocktail of ordinary, accurate statements made it “plausible” that physicians would hear an inducement message to prescribe for “any” approved use of generic Vascepa, including the patented CV indication. Reality check: physicians are not induced by investor press releases; pharmacist substitution statutes don’t consult marketing copy; and AB rating means therapeutic equivalence for labeled uses, not carte blanche for everything on the brand label.[5] But never mind: this case was on a motion to dismiss and discovery awaits.

The Market Realities Everyone Knows (And the Law Is Supposed to Respect)

Here’s what actually happens in the real world and why it matters:

Pharmacist substitution is driven by therapeutic equivalence and state law, not by press releases. Across the country, pharmacists substitute AB-rated generics for the brand unless a prescriber forbids it. Most prescriptions don’t include an indication, and no one calls IR for interpretive guidance on marketing blurbs.

AB rating is about equivalence for the labeled use. That is the entire point. The Food Drug and Cosmetic Act and FDA practice make this boring by design: approved generic = same active ingredient, same labeling (minus the carve-out), same therapeutic effect for the approved use. Pretending that AB rating “suggests” off-label, patented uses is not how any of this works.

Skinny labels exist so one patented use doesn’t block generics for the non-patented ones. Congress chose section viii precisely because some off-label use will happen in a mixed-patent world—and because the right answer is to prohibit promotion of the patented use, not to criminalize existence. That’s why “active inducement” requires actual active steps that target the patented use.

Investor communications aren’t physician detailing. Citing total brand sales, describing a product as the “generic version,” and noting the obvious—Vascepa has more than one indication—are the kind of statements the market requires, not inducement scripts. If the bar is “don’t mention reality,” then the only safe investor relations update is to hang up.

What the Case Actually Turns On: Inducement vs. Inference

Under § 271(b), inducement requires active steps directed to the patented method. See, e.g., Global-Tech[6]: “affirmative steps to bring about the desired result.” And Grokster[7] told us that promotional material may support a finding of intent, but certainly doesn’t carry the day.

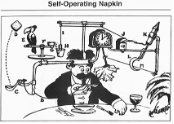

Here, neither the label (carved out) nor the cited statements mention reducing CV risk, using the drug with a statin, or any other step of the asserted methods. The theory is a Rube Goldberg[8] of inference: investors read a press release, doctors somehow take from that an instruction to prescribe for the CV indication, pharmacists substitute a skinny-labeled generic without knowing the indication, and we call that “active inducement.” That is not inducement. That is economics.

The Solicitor General’s View: This Isn’t Close

The SG urged cert and a reset: skinny labels are a core part of Hatch–Waxman’s balance, and generic manufacturers must be able to:

Use carved-out labels that omit patented uses.

Accurately describe their product as the brand’s generic version.

Provide truthful, high-level market information to investors.

None of that is an “active step” to induce the patented use. If that becomes actionable, section viii is a Potemkin village, and the rational response for generics is to avoid carve-outs, delay entry, or settle meritless claims rather than risk nine-figure “lost profits” calculated as if every infringing prescription was their fault. If that sounds like policy made by pleading standard, that’s because it is.

Why This Matters Beyond Fish Oil

Pleading games become pricing power. If “generic version” + public sales data = a plausible inducement claim, then routine disclosures invite litigation, discovery, and leverage that Congress explicitly designed section viii to avoid.

Damages distortions turbocharge risk. Current Federal Circuit damages approaches can translate a sliver of alleged influence into all infringing sales. That’s not a market correction; that’s a cudgel against entry.

This won’t stop at pharma. If comparative or compatibility statements plus public market facts can plausibly “induce,” expect inducement-by-press-release theories in any market where a product interoperates with—or competes against—something covered by a method patent.

Practical Implications While We Wait for the Court

For generics operating under section viii, keep doing the boring, correct things and write like a regulator is reading over your shoulder:

Maintain a genuine carve-out and scrub the label for stray clinical references that could be misconstrued as instructing the patented use.

Keep AB-rating and “generic version” statements accurate, and pair them with plain disclaimers that approval is for fewer than all brand indications.

Segregate investor communications from HCP-directed materials and avoid implying therapeutic scope beyond the labeled use.

For brands, calibrate litigation posture to actual promotion:

The SG’s position and statutory structure both make clear: conventional market facts are not “active steps.” Claims survive when there’s targeted messaging that maps to the claimed steps; they should not when the “inducing act” is merely existing in a market with pharmacist substitution.

The Bottom Line

This petition is the clean vehicle GSK wasn’t. The label is “skinny enough;” the alleged “inducing” statements are generic to the point of yawns; and the SG has put a bright line where it belongs: between active inducement of a patented use and the everyday market speech that Congress fully expected in a skinny-label world. If the Supreme Court restores that line, section viii can function as designed. If not, prepare for a golden age of inducement-by-innuendo—and higher prices while generics think twice about entering at all.

If you have questions about this Client Alert or are interested in additional details or guidance, please reach out to Greg Chopskie (greg.chopskie@pierferd.com) or your regular PierFerd contact for assistance.

This publication and/or any linked publications herein do not constitute legal, accounting, or other professional advice or opinions on specific facts or matters and, accordingly, the author(s) and PierFerd assume no liability whatsoever in connection with its use. Pursuant to applicable rules of professional conduct, this publication may constitute Attorney Advertising. © 2025 Pierson Ferdinand LLP.

[1] 21 U.S.C. § 355(j)(2)(A)(viii)—the so-called “skinny” or “little eight” label.

[2] Warner-Lambert Co. v. Apotex Corp., 316 F.3d 1348 (Fed. Cir. 2003).

[3] GlaxoSmithKline LLC v. Teva Pharms. USA, Inc., 7 F.4th 1320 (Fed. Cir. 2021).

[4] Amarin Pharma, Inc. v. Hikma Pharms. USA Inc., 104 F.4th 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2024).

[5] AB ratings mean a generic version of a drug “can be expected to have the same clinical effect and safety profile [as the branded drug] when administered to patients under the conditions specified in the labeling.”) FDA, Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, Preface to the Forty-Fifth Edition; see also 21 CFR 314.3(b).

[6] Global-Tech Appliances, Inc. v. SEB S.A., 563 U.S. 754 (2011).

[7] MGM Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 545 U.S. 913 (2005).

[8]