Supreme Court Petition Targets “After-Developed” Technology in Patent Validity—and a Deep Split at the Federal Circuit

Summary. A closely watched petition for certiorari asks the Supreme Court to resolve a fundamental question in patent law: may courts consider after-developed technology when assessing validity under Section 112’s written description and enablement requirements? The petition arises from the Federal Circuit’s decision in In re Entresto, which sustained validity while accepting a broad infringement construction that captured a later-invented chemical “complex.” The case spotlights a long‑standing division in Federal Circuit precedent over whether claim scope must be treated consistently for infringement and validity when later-arising embodiments are at issue. The outcome could reshape patent drafting, litigation strategy, and freedom-to-operate assessments across life sciences, high tech, and beyond.

The Question Presented

Whether, in a patent-infringement suit, a court may consider after-arising (after-developed) technology to hold that the patent is invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a). The petition emphasizes that neither the Supreme Court nor the Federal Circuit sitting en banc has squarely resolved this issue, despite decades of inconsistent panel decisions.

Why This Matters

Section 112 embodies the patent bargain: claim scope must be commensurate with what the patentee described and enabled. When later-developed embodiments fall within the literal claim language, two core principles collide: the norm that claims are construed the same for infringement and validity, and the concern that patentees cannot be expected to describe or enable technology that did not yet exist. The choice of rule affects whether broad, generic, or functional claims can be leveraged to capture future innovations, and whether those claims withstand validity scrutiny.

The Case Catalyst: In re Entresto

The patent claims a “combination” of valsartan and sacubitril. Years after filing, researchers discovered a non‑covalent “complex” of the two—an embodiment with distinct properties. The district court construed “combination” broadly to include complexes, leading to a stipulation of infringement, but found the claims invalid for lack of written description. On appeal, the Federal Circuit reversed the written-description ruling and affirmed against enablement and obviousness challenges—while embracing reasoning that treated the later-arising complex as outside the validity analysis. This created asymmetry: broad for infringement, narrower for validity. The court denied rehearing en banc.

The Split in the Federal Circuit’s Case Law

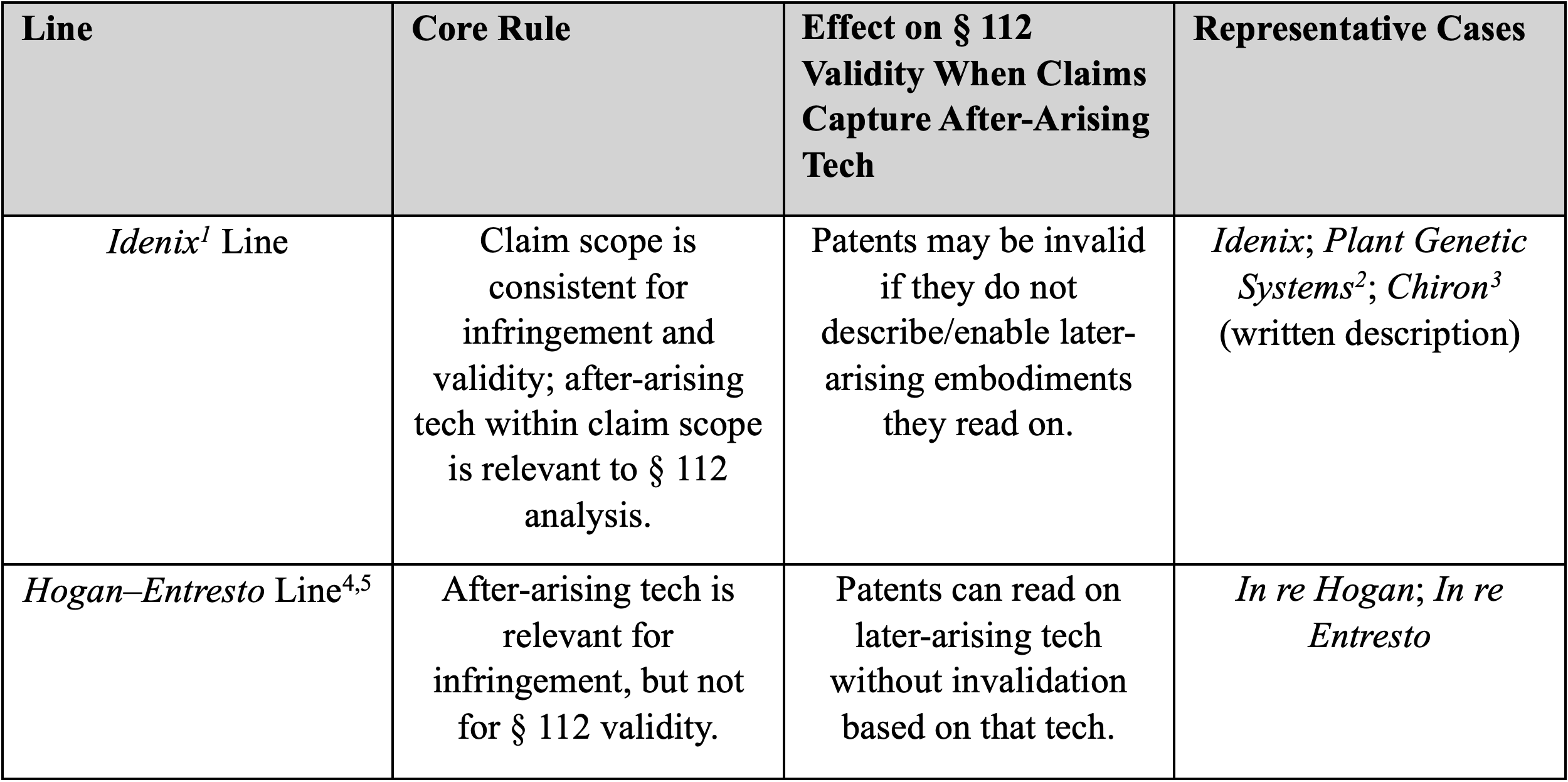

The petition and multiple amicus briefs identify conflicting lines of authority that have produced uncertainty across industries.

Two principal, conflicting approaches

Additional, inconsistent strands

A narrowing construction to avoid after-arising tech and find no infringement (e.g., Schering[6]).

A broad construction to encompass after-arising tech for literal infringement (e.g., SuperGuide[7]).

The upshot is doctrinal tension about whether courts should adopt time-fixed claim meaning keyed to the filing date and how to reconcile claim construction with Section 112’s disclosure obligations.

How We Got Here: Anchoring Principles and Precedents

The Supreme Court has emphasized that patentees must enable the full scope of their claims and that the patent bargain requires commensurability of disclosure and exclusivity. It has also cautioned against treating claims as a “nose of wax” whose scope shifts to suit occasion.

Historical precedent illustrates how after-arising embodiments can expose overbreadth: when a broad genus claim captures a later-developed species, the failure to describe or enable that species may reveal a Section 112 defect.

Recent enablement jurisprudence reinforces that if a claim covers a broad class, the specification must enable a skilled artisan to make and use that full scope without unreasonable experimentation. The decision did not resolve the role of after-arising embodiments in that analysis.

Key Arguments in the Cert Petition and Amici

Predictability and symmetry: A single claim scope should govern both infringement and validity; if later-arising embodiments are captured for infringement, they should count in the Section 112 analysis.

The patent bargain: Allowing patentees to capture after-arising technology without commensurate disclosure confers windfalls, chills design-around innovation, and invites strategic assertion of old priority dates against new technology.

Policy impacts: The uncertainty burdens innovators and investors across technology areas, and in pharmaceuticals may delay generic entry and increase costs.

Proposed doctrinal solutions vary. Some amici favor the Idenix line (consistent scope and Section 112 scrutiny), while others advocate limiting literal scope or employing doctrines such as the reverse doctrine of equivalents to avoid windfall capture of non-enabled, later-arising embodiments.

What’s at Stake for Innovators and Patent Owners

Claim drafting and prosecution. Broad genus or functional claims that may later sweep in unforeseen embodiments face heightened risk if the Court embraces a symmetry rule. Applicants may need more concrete exemplification, prophetic examples, or claim tailoring to sustain breadth.

Litigation strategy. A party that presses for a broad construction to secure infringement may risk invalidation under Section 112 if later-arising embodiments are within scope. Conversely, a narrowing construction to avoid after-arising embodiments may foreclose infringement.

Portfolio management. Companies may revisit continuation strategies, terminal disclaimers, and related filings to ensure adequate disclosure support for foreseeable technology trajectories.

Freedom to operate. Design-arounds leveraging new materials, architectures, or methods may be more defensible if the Court requires commensurate disclosure for later-arising embodiments included within literal scope.

Industry-specific impact. Life sciences disputes involving genus claims to molecules, antibodies, or combinations, and high-tech claims with functional language, are particularly exposed.

Practical Takeaways Now

Reassess risk where asserted or critical claims use broad, categorical, or functional language that could encompass later-arising embodiments. Map those embodiments to the original disclosure for both written description and enablement.

Calibrate claim construction positions with Section 112 risk. Consider whether the record supports a construction aligned with what a skilled artisan would have understood at filing, and the implications for validity symmetry.

Fortify specifications. For pending and future applications, provide richer structural and methodological disclosure, reasoned rationale, and, where appropriate, predictive exemplars that support known trajectories of technological development.

Preserve arguments. In ongoing litigation, preserve both claim construction and Section 112 issues. Avoid asymmetry that courts may disfavor if the Supreme Court grants review and clarifies the rule.

What to Watch

Grant of certiorari. Multiple amicus briefs—from industry coalitions, public interest organizations, and academics—underscore the systemic importance and enhance the likelihood of review.

Framing of the rule. The Court could endorse (i) claim-scope symmetry for infringement and validity; (ii) limits on literal scope to embodiments understood at filing; or (iii) a doctrinal safety valve, such as the reverse doctrine of equivalents, to avoid windfalls without categorical invalidation.

Interaction with recent enablement law. Any ruling will have to harmonize with the requirement to enable the full scope of the claims and may clarify how “reasonable experimentation” applies when the embodiment emerges later.

Bottom Line

The Supreme Court is being asked to resolve whether later-developed technology that falls within the literal scope of a patent can and should be considered in determining validity under Section 112. A decision aligning infringement and validity scope would restore coherence to a fractured body of law and reshape both claim drafting and litigation strategy. Companies should evaluate exposure and adjust prosecution and enforcement approaches in anticipation of greater symmetry between what a patent claims and what it must teach.

If you have questions about this Client Alert or are interested in additional details or guidance, please reach out to Greg Chopskie (greg.chopskie@pierferd.com) or your regular PierFerd contact for assistance.

This publication and/or any linked publications herein do not constitute legal, accounting, or other professional advice or opinions on specific facts or matters and, accordingly, the author(s) and PierFerd assume no liability whatsoever in connection with its use. Pursuant to applicable rules of professional conduct, this publication may constitute Attorney Advertising. © 2025 Pierson Ferdinand LLP.

[1] Idenix Pharms. LLC v. Gilead Scis. Inc., 941 F.3d 1149 (Fed. Cir. 2019).

[2] Plant Genetic Sys., N.V. v. DeKalb Genetics Corp., 315 F.3d 1335 (Fed. Cir. 2003).

[3] Chiron Corp. v. Genentech, Inc., 363 F.3d 1247 (Fed. Cir. 2004).

[4] In re Hogan, 559 F.2d 595 (C.C.P.A. 1977).

[5] In re Entresto, 125 F.4th 1090 (Fed. Cir. 2025).

[6] Schering Corp. v. Amgen Inc., 222 F.3d 1347 (Fed. Cir. 2000).

[7] SuperGuide Corp. v. DirecTV Enters., Inc., 358 F.3d 870 (Fed. Cir. 2004).